|

The modules stack up fast

Scheduling the exact day for module arrival was complicated by weeks of rain. A lead

person from the module manufacturer came down to manage the local set up crew. His careful briefing developed good crew coordination.

The next two days were exciting for us after all our months of planning. The plastic

wrapping on each module was removed, a huge crane lifted each unit, and the set-up crew guided each into place. The crew pushed to do the job and set the six modules in two and a half days. We kept

sneaking inside to see how everything lined up and to check the features that we had ordered but had never seen. After they filled in the gables ends and pulled off interior supports, the crew

strapped the modules to the foundation with hurricane ties on 16” centers.

Although the modular and the timberframe sections were freestanding, the

crew also tied the sections together on exterior corners, using three galvanized angle brackets per story. Although the modular and the timberframe sections were freestanding, the

crew also tied the sections together on exterior corners, using three galvanized angle brackets per story.

The site-built roof extensions, called overbuilds, were the last link between

the post and beam’s exterior and the newly set modules.

Â

Trim work unites disparate sections

After so much activity, the pace of the finishing work seemed to drag on.

But as the garage, porches, and cedar clapboards were added, our house became more horizontal, bleontrastnding into the wooded setting. When

painted, the white trim and porch details provided a nice contrast.

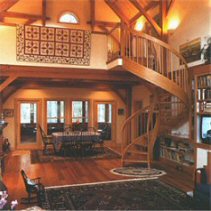

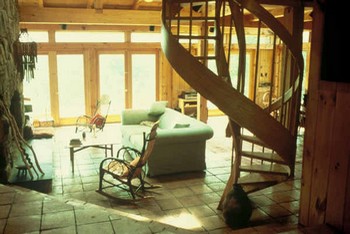

Inside, openings between the modules and the great room were finished. Pined window frames and moldings in

the great room were stained to match those in the module. We indulged ourselves and bought clear heart pine for the great room floor.

When the spiral staircase was installed on the newly varnished wood and we could ascend to the balcony above,

we knew that the parts of our house had finally knit together as planned.

Once the dust settled, we crunched numbers to see where the money had gone. After factoring in porches,

heated basement, and garage, we were surprised by the results.

The modular part of the house cost 12 % less than

the timbedr frame - a figure probably due to the kitchen and bathrooms. Tile and hardwood floors, solid surface counters, the geothermal heating system and a 100 ton crane pushed up the modular

price. Still, if we had timberframed the entire house, the cost would have been much higher.

By using modular construction, we saved a great

deal of time and we were also able to contol cost and quality. We saved money by taking on many of the management tasks ourselves; our sweat equity

also included a big chunk of the electrical work and some finish carpentry.

Free-lance writer Libby Schroeder lives in Moorsville, NC with her husband John

|